By Maria Koniotou

THE repatriation of the last complete fragments from the nearly 1,500-year-old Kanakaria mosaics made 2018 a significant year for cultural heritage, according to Cypriot art historian Maria Paphiti

In an interview with the Cyprus News Agency (CNA), published on Saturday, Paphiti said the repatriation of the mosaics, stolen after 1974 from the church of Panagia Kanakaria in Lythrangomi, in the Famagusta district in the north, was important not only for Cyprus “but for the world cultural heritage too”.

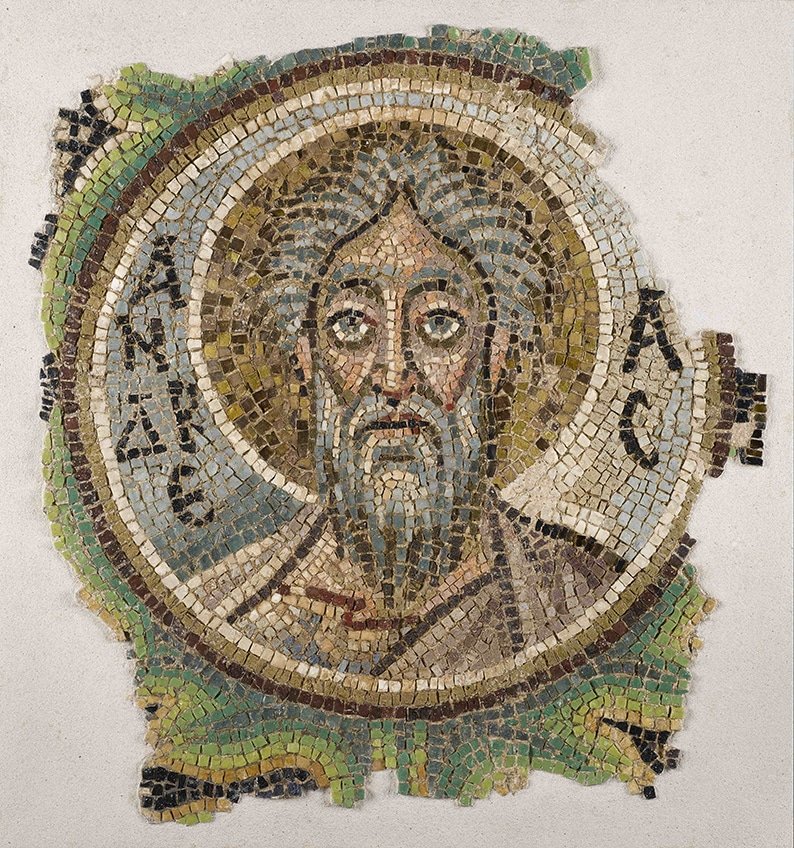

In 2014 it was Paphiti who identified the fragment of Apostle Andrew from the Church’s 6th century mosaic decoration, which was returned to the island in April. She said it was “the most emblematic of all and perhaps the most important treasure that had been missing from Cyprus, a symbol of our looted cultural heritage in recent years.”

In November, Dutch art investigator, Arthur Brand, returned to the Embassy of Cyprus in The Hague the mosaic of Apostle Mark, which was subsequently repatriated. Also, in September, the first liturgy was held in the church of Panagia Kanakaria since 1976, when the last Greek Cypriots that remained there after the 1974 Turkish invasion, were forced by the Turks to leave their village.

“I believe that the three above events allow us to compare 2018 with 1989, a landmark year for Kanakaria, during which the Republic of Cyprus and the Church of Cyprus won a trial against art dealer Peg Goldberg, who had bought four fragments of the mosaic from the Turkish smuggler Aydin Dikmen, with the intention of selling them for 20 million dollars to the Paul J. Getty Museum,” Paphiti said.

She said the Kanakaria trial, held in Indianapolis, US, was among the first high-profile cases of claiming cultural heritage worldwide. It set a precedent and it is referred to in a similar fashion to the present day. The four fragments won in 1989 depict the upper part of the body of Christ, an archangel and the Apostles James and Matthew.

Asked how she got involved with the Kanakaria case, Paphiti explained that as an art consultant with specialisation in Byzantine and Russian art, she works with collectors in the respective fields from different countries.

“A client of mine purchased a collection of icons and religious works of art, one of which was the mosaic of Apostle Andrew. I identified it when I was asked to study his new acquisitions. I wrote a report and then I explained to the client that the mosaic worth more than six million euros had been looted from occupied Cyprus. He was unpleasantly surprised and initially his reaction was negative because he himself had acquired the collection by lawful proceedings,” she said.

“Then, after having assessed the situation, the client decided to hand over the mosaic for a token sum that would cover the costs of storage, insurance and maintenance while the artwork was in his possession. This settlement was indeed fair because under Article 6 of the 1995 UNIDROIT Convention the possessor is entitled to demand a reasonable compensation.”

She added that the alternative would be for Cyprus and its Church to proceed to litigation that would have probably ended victoriously, but would have been extremely time consuming and would have cost more than the €50,000 compensation given to the possessor. Two donors, Dr Andreas Pittas and Roys Poyiadjis paid the amount, while the legal services were provided free of charge by lawyer Michael Kοrelis. As a result, the cost to Cyprus and the Church was nil.

Paphiti emphasised that “everyone, and especially the professionals in the field of art, must operate in an ethical and transparent way, but should also keep a watchful eye to identify artworks that are illegally marketed, whether they come from our country or elsewhere.”

As far as the missing pieces of the mosaic are concerned, she said there is not much left. Yet, they are all important, because without each and every fragment, the composition that existed in the sanctuary apse pre-1974 cannot be recreated.

Still missing are the mosaics of Apostle Philip, that was in a fragmented state before the pillaging, an unidentified saint, the lower part of Christ`s body and a non-figural decorative fragment, she added.

Paphiti explained that the Kanakaria mosaics, dating back to the beginning of the 6th century, were of great importance to world art history because they are among a handful of Christian artefacts that survived iconoclasm (726-843 AD), thus providing vital information for the portrayal of divine persons during the early Byzantine era.

The mosaic composition that adorned the sanctuary apse of Kanakaria church depicted the enthroned Virgin holding Christ, not as an infant, but as a young boy, framed by a frieze showing portraits of the Apostles in medallions.

She added that the cultural significance of the mosaic was known for a long time. She said

further proof was the fact that the British colonial administration in Cyprus issued in 1955 a stamp that represented the church of Kanakaria.

Paphiti added that the Cyprus Post in 1967 released a stamp dedicated to the mosaic of Apostle Andrew, who stood out from the rest of the Apostles, due to his unique features, namely, his long beard, dishevelled hair and blue eyes.

Paphiti visited the church in Lythrangomi in September, when a liturgy took place there for the first time after 42 years. “Since my childhood, I listened with great interest discussions about the pillaging of our cultural heritage, especially the case of Kanakaria and the occasional repatriation of its fragments,” she said.

“As an art historian I became even more aware of the church`s great importance. Also, due to my involvement in the repatriation of the Apostle Andrew fragment, I developed an emotional and personal relationship with the monument,” she added.

“My visit to Kanakaria…was a pilgrimage, a return to a place that seemed familiar because of my involvement in the matter, yet one, which in fact, had been unknown to me,” she said.