This is one of a series of articles from our new feature ‘Background briefing: The Divided Island‘. It is a comprehensive interactive information guide on the Cyprus problem.

1955 – 1959

The campaign has mass Greek Cypriot support and is backed by wide-scale civil disobedience. Many Greek Cypriots leave the police force, either in solidarity with Eoka or because of intimidation.

The British colonial authorities replace them with recruits from the smaller Turkish Cypriot community, which is opposed to enosis and prefers to stay under British rule. Britain also says Turkey should have a say in Cyprus’ future. There are periodic outbreaks of inter-communal violence and the Turkish Cypriots begin to pursue taksim (partition) and union with Turkey.

With Turkish support, they form an underground guerrilla organisation, the Turkish Resistance Movement (TMT), whose declared aim is to prevent union with Greece.

Cyprus’ geostrategic importance to Britain soars after the loss of Suez in 1956. But London comes to believe that its strategic interests can be met by having military bases on the island rather than having the island as a base. It veers towards a policy of independence for Cyprus while offloading the problem on the “motherlands” – Greece and Turkey, which draft the independence agreements.

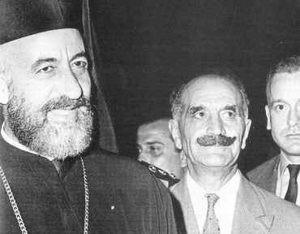

Cyprus gains independence from Britain on 16 August. Britain, Turkey and Greece become guarantor powers of the island’s independence, sovereignty and territorial integrity under the terms of Cyprus’ constitution. Britain retains sovereignty over two military bases covering 98 square miles. Archbishop Makarios is the first president of an independent Cyprus and Dr Fazil Kucuk, the Turkish Cypriot leader, is vice-president. Cyprus becomes a member of the United Nations.

1961

There is an outbreak of inter-communal fighting on December 21, 1963. A precarious ceasefire is agreed on Christmas Day. A “green line” is drawn through Nicosia on 30 December to mark ceasefire lines. The Turkish Cypriots withdraw from the Cyprus Republic.

1964

autonomous administration. The Greek Cypriots alone are now represented in the government, which is recognised internationally as the island’s only legitimate authority. Turkish Cypriots say they were forced out; Greek Cypriots say they left to set up their own administration. The Greek Cypriots re-introduce the demand for Enosis.

A multinational United Nations peacekeeping force, Unficyp, is established in March but struggles to contain inter-communal violence. Turkey has been preparing for a military invasion, which is averted in early June only by a robust warning from the US president, Lyndon Johnson. He fears such Turkish action would lead to war between Turkey and Greece – the US’s allies in Nato – and so weaken the alliance’s south-eastern flank.

The Greek Cypriots establish a National Guard, introducing compulsory military service in June. Makarios starts making overtures to the Soviet Union.

Greece sends an army division of some 10,000 troops to Cyprus on the grounds that it will protect the island, but Athens is also concerned that Cyprus is coming under the influence of the Soviet Union.

At US president Lyndon Johnson’s initiative, there are talks between Greece and Turkey for a Cyprus solution, with a former US secretary of state, Dean Acheson, serving as mediator. The “Acheson Plan” envisages the union of Cyprus and Greece, while up to three cantons would be established for the Turkish Cypriots, over which they would have full administrative control.

There is heavy fighting in August when the National Guard – now commanded by the former Eoka leader General George Grivas – attacks the fortified Turkish Cypriot enclave of Kokkina-Mansoura on the northwest coast, which is being used to smuggle in arms from Turkey.

In response, Turkish jets attack two Cypriot patrol boats and bomb National Guard positions and Greek Cypriot villages in the area. Fifty-three Greek Cypriots are killed, including 28 civilians. After these incidents, Acheson abandons his initiative.

1967

The ‘Kofinou Crisis’ in mid-November brings Greece and Turkey to the brink of war. It erupts when a large National Guard force attacks Turkish Cypriot positions in and around the mixed village of Ayios Theodoros – where Turkish Cypriot fighters had prevented Greek Cypriot police patrols – and the nearby Turkish Cypriot village of Kofinou. These villages are considered strategically important because they are located at the junction of the main roads from Nicosia and Larnaca to Limassol.

The Greek Cypriots fear the Turkish Cypriots are trying to create a new enclave in the area. Twenty-seven Turkish Cypriots die in the fighting. Turkey threatens military intervention and its fighter jets fly over Nicosia. Greece is persuaded to withdraw several thousand troops from Cyprus along with Grivas, the National Guard commander.

1968

Seeking a fresh mandate, Makarios calls elections to be held in February 1968 and secures 95.45 per cent of the vote, trouncing his only rival who ran on a platform for enosis.

Makarios appoints Glafcos Clerides, president of the House of Representatives, to hold UN-sponsored talks with Turkish Cypriot leader Rauf Denktash which open in Beirut in June.

1970

1971

1972

1974

On July 3 Makarios publicly accuses the junta of using Greek officers in the National Guard to subvert his government and demands that Athens withdraw 650 of them immediately.

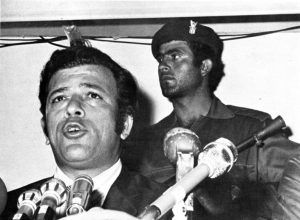

Instead, on 15 July, Greek officers in the National Guard, directed from Athens, launch a coup against Makarios aimed at enosis. He escapes to London. Nicos Sampson, a notorious ex-Eoka gunman feared by Turkish Cypriots, is installed as president. Makarios accuses Greece at the UN Security Council of invading Cyprus.

On July 20 Turkey invades, invoking the 1960 Treaty of Guarantee.

The coup collapses on 23 July. The military junta in Greece falls; civilian rule returns. Sampson is forced to step down and Glafcos Clerides becomes acting president.

Turkey launches the second phase of its invasion on August 14 with its forces advancing rapidly to seize 36.2 per cent of Cyprus. Ceasefire lines established on August 16 have not since changed. Between them marks the UN-controlled buffer zone.

165,000 Greek Cypriots are displaced from northern Cyprus while 45,000 Turkish Cypriots move north within a year.

Makarios returns from London in December.

1975

Turkish Cypriots declare the “Turkish Federated State of Cyprus” with Denktash as its leader.

1977

Makarios dies in August and is succeeded by Spyros Kyprianou.

1978

1979

1983

1985

1988

1989

1990

1992

1993

Clerides and Greece’s prime minister, Andreas Papandreou, declare a ‘Unified Defence Dogma’. Joint military exercises begin.

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

The European Court of Human Rights, reinforcing its decision in 1996, orders Turkey to pay compensation to a Greek Cypriot refugee, Titina Loizidou, for barring her access to her property in Kyrenia. Turkey fears the landmark ruling – which does not forfeit her rights to the property – will open the floodgates for countless refugees to file lawsuits. In December 2003, Turkey pays Loizidou more than $1m compensation.

Clerides appoints Vassiliou as chief negotiator for EU accession negotiations, which are initiated in April. Turkish Cypriots reject an offer by Clerides that they join the negotiating team.

1999

Proximity talks begin between Clerides and Denktash. The aim is that Cyprus will be reunited before it joins the EU.

2002

Kofi Annan, the UN secretary general, presents a comprehensive peace plan in November to reunite Cyprus as a bi-zonal, bi-communal federal republic with a single sovereignty.

A December EU summit in Copenhagen invites Cyprus to join the bloc in 2004.

Concerned they could miss out on EU entry, Turkish Cypriots demonstrate in huge numbers in late 2002 and early 2003, demanding that Denktash must either accept the Annan Plan or resign.

2003

Annan invites Papadopoulos and Denktash to the Hague in March to ask whether they accept his reunification plan. Papadopoulos says he does but under certain conditions, while Denktash rejects it in its entirety and the talks collapse.

Denktash unexpectedly allows access to ordinary Cypriots across the “green line” for first time in 29 years. Tens of thousands of Greek and Turkish Cypriots cross: there are scenes of high emotion and remarkable goodwill.

2004

Papadopoulos and Denktash agree at a February meeting in New York to a new procedure aimed at putting the Annan Plan to twin referendums before Cyprus joins the EU on May 1. The referendum on the Annan Plan was held on April 24 following negotiations in Burgenstock, Switzerland. After a bitter yes/no campaigns, Greek Cypriots voted 76 per cent against the solution plan and 65 per cent of Turkish Cypriots voted in favour.

Cyprus joined the EU on May 1 against the backdrop referendum failure and the overt disappointment of the EU and the rest of the international community.

2005

Turkey begins accession negotiations with the EU in October.

2006

The EU partially suspends Ankara’s accession negotiations over Turkey’s refusal to open its ports and airports to traffic from Cyprus, freezing talks on eight of 35 negotiation chapters (policy areas).

UN-backed talks between President Tassos Papadopolous and Turkish Cypriot leader Mehmet Ali Talat agree a series of confidence-building measures and contacts between the two communities.

2008

Cyprus adopts the euro in January.

Tassos Papadopoulos loses presidential elections in February and is replaced by Demetris Christofias, the Akel leader.

Talks begin between Christofias and Turkish Cypriot leader Mehmet Ali Talat, who succeeded Denktash in April 2005. Talat’s CTP party has close links with Akel. It is the first time that leaders who are ideologically close are negotiating an end to the Cyprus problem.

The two leaders also negotiated the setting up of bicommunal technical committees that discuss day-to-day issues related to such common topics as crime, cultural heritage, education and health.

The crossing on Ledra Street, a symbol of the island’s division, re-opened in April for the first time since 1964.

2010

Encouraged by progress in talks between Christofias and Talat, the UN Secretary-General, Ban Ki-moon, visits Cyprus at the end of January. The two leaders assure him of “their shared commitment to a comprehensive solution as early as possible”.

Talat is ousted in Turkish Cypriot ‘presidential’ elections by Dervis Eroglu, a hardliner.

2011

Cyprus starts exploratory offshore drilling for oil and gas in September. Turkey responds by sending an oil research vessel with a military escort into Cyprus’ exclusive economic zone (EEZ). Christofias and Eroglu meet the UNSG in New York.

2012

The two leaders met in Greentree, New York again in January with the UNSG. He said he was “disappointed with the lack of progress”, and conveyed this disappointment to the leaders at Greentree in January. Later in the year, with no convergences, Eroglu said his side wanted a timeframe for results. Christofias said no, and besides was not running again for election in February 2013.

2013

Disy party leader Nicos Anastasiades was elected president in February, ousting Demetris Christofias and opening the way for yet another process on the Cyprus issue, this time, and for a while, with then Turkish Cypriot leader Dervis Eroglu who was much more hardline than his predecessor Mehmet Ali Talat.

Anastasiades was seen as a moderate having supported the Annan plan, which did not go down well within Disy as a whole. The first months of his presidency were however taken up with the economic crisis and the haircut on bank deposits. Thus, he did not get around to starting a new Cyprus process until October that year. Predictably, nothing came of it.

2014

Anastasiades and Eroglu issue a “Joint Declaration” setting the basis for new, UN-facilitated negotiations. It states the goal is to establish a bi-communal, bi-zonal federation with political equality, a single citizenship and a single sovereignty.

Anastasiades suspends reunification talks with Eroglu in October after Turkey sends a research vessel and warships into Cyprus’ EEZ.

2015

Mustafa Akinci wins Turkish Cypriot ‘presidential’ elections on a pro-reunification platform in April, leading to a resumption of Cyprus peace negotiations in May with Nicos Anastasiades in a development that everyone had high hopes for.

2016

Cyprus exits its EU-IMF bailout programme in March. UN-facilitated negotiations to reunify Cyprus intensify and make good progress throughout the year. Anastasiades and Akinci fail to agree on territorial adjustments during November talks in Mont Pelerin, Switzerland. But both commit to continue negotiating.

On Dec 1 Anastasiades and Akinci agree to resume negotiations in Nicosia and to meet in Geneva on January 9. Two days later they are to present maps on their respective proposals for the internal boundaries of a future federation.

2017

Two years of talks between Nicos Anastasiades and Mustafa Akinci finally paid off when the biggest conference on Cyprus since Burgenstock in 2004 was called for July, with a second real chance to secure a settlement at Crans-Montana, also in Switzerland.

But before that, due to “unprecedented substantive progress” the UNSG convened first a conference on Cyprus in January 2017 in Geneva, according to the UN chief. By January 2017, the contours of a bizonal, bicommunal federation with political equality were well known and had been largely agreed, he said.

The meetings held between January 9 and 12 were a “watershed moment” in the process, he said. For the first time in the history of the negotiations, the two leaders presented each other with their preferred maps of the internal administrative boundary. “The presentation of maps was an important moment both in itself but also in that it was seen by both sides as a sign that the process was moving towards the ‘end game’ the UNSG report said.

On the basis of these commitments, the Conference on Cyprus reconvened on June 28 in Crans-Montana, Switzerland, with the participation of Mr. Anastasiades and Mr. Akıncı, the Ministers for Foreign Affairs of Greece, Turkey and the United Kingdom and the Vice-President of the European Commission in his capacity as observer. With the aim of arriving at a strategic agreement on all major outstanding issues.

Day 9 of the talks began with the return of United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres in a bid to rejuvenate the negotiations. Cue ubiquitous photo op with the leaders, the foreign ministers of Turkey and Greece, the EU’s Federica Mogherini and Britain’s Sir Alan Duncan.

Turkish Cypriot leader Mustafa Akinci told reporters: “Today is not a day to engage in the blame-game. It is the day to help each other and see if we can reach an agreement. We don’t know whether we will have the same opportunity tomorrow.” Twenty-four hours later he had completely changed his tune.

You knew things were not going well when lunch was pushed back and Guterres had to meet separately with the leaders and the different factions. This went on all afternoon. British Permanent Representative to the United Nations Matthew Rycroft said that Guterres “is straining every muscle to get Cyprus talks over the lines”. He would not have been the first.

But like all processes before it, Crans-Montana came crashing down in the early hours of July 7- Day 10.

Cypriots woke up that Friday morning to the ashes of ten days of make-or-break talks, which crashed and burned in dark of night.

Both sides accused the other of being responsible for the gigantic failure of talks that seemed to swing between ‘almost there’ to ‘never there’ from day to day until an exhausted and clearly disappointed Guterres, after 15 hours of negotiating, called a halt at 3.15am Cyprus time.

Guterres’ news conference lasted only 3.5 minutes. He said he could not isolate a particular issue as the death knell for the talks, but was firm that the conference was over and he wished “the best for all the Cypriots north and south”.

UN Special Adviser Espen Barth Eide tweeted on his way out of Crans-Montana: “Close, but not close enough: A somber mood as delegations leave #CransMontana, after 10 days, without agreement”.

- Guterres deeply sorry, wishes the best for Cypriots north and south

- July 2017: Picking up the pieces from Crans-Montana

It was almost as devastating as the ‘no’ vote in the 2004 referendum. That had set negotiations back for 13 years, Crans-Montana, although no one knew at the time, put the Cyprus issue back into the deep freeze for more years to come.

Then the real fun began, statements, rumours, innuendo and the ubiquitous blame game. Both sides accused the other of being responsible for the gigantic failure of the talks that had seemed to swing between ‘almost there’ to ‘never there’ from day to day.

Each side blamed the other for weeks over a long, hot summer, (and months and years after that) waiting for Guterres to put the other straight in his eventual report, which came on September 30.

The carefully-worded verdict: A historic opportunity was missed in Crans-Montana and no blame was assigned. So, the Swiss negotiations like all those before them were consigned to the dustbin of Cyprob history, and another special envoy has gone to the diplomat’s Cyprob graveyard.

2018

The year started with the re-election of Nicos Anastasiades for a second term in February, despite the massive failure at Crans-Montana only seven months previously.

Post-election analysis appeared to show that voters wanted continuity.

In June 2018, in an attempt to kick-start new talks, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres appointed Jane Holl Lute as his new adviser. Her mission involved shuttle diplomacy between Nicos Anastasiades and Mustafa Akinci, and Athens, Ankara and the UK to prepare “terms of reference”. She was unable to bridge the gap given the still-fresh fallout from Crans-Montana less than 12 months previously. Guterres noted in his year-end report “the lack of progress towards a settlement since the conclusion of the Conference on Cyprus in July 2017”.

He said that ten months after Crans-Montana no further progress had been made towards a settlement. He also spoke of “diminished trust between the leaders and their respective communities” and the continued absence of dialogue.

Late in the year, Anastasiades suddenly started talking of a ‘decentralised’ or ‘loose’ federation but seemed to be unable to say exactly what that meant. Despite this, he was insisting he wanted the talks to go ahead where they left off although there was mounting pressure on him to come clean and be honest with people on what he was really seeking.

He did agree with Akinci in October to open two new crossing points – the first in eight years – at Dherynia and Lefka, which were inaugurated on November 12.

2019

There was zero progress on the resumption of talks in the first half of 2019. Any prospect for a resumption of talks before June was also put on ice early in the year due to the European elections slated for the end of May, and elections in Turkey.

In February, Greece and Turkey agreed try and defuse tensions through dialogue, including Cyprus but the continued dispute over hydrocarbons exploration and exploitation in the Eastern Mediterranean remained a thorny issue.

Nicos Anastasiades and Turkish Cypriot leader Mustafa Akinci met at the residence of UN Special Representative Elizabeth Spehar on February 26 to discuss the terms of reference but nothing substantial came from the meeting other than a feeble attempt to make it look like they were achieving something.

They met again in August in Nicosia and agreed to continue a dialogue and engage with UN envoy Jane Holl Lute but they were not getting along at all.

In November, the UNSG, Antonio Guterres and the two leaders met for an informal dinner in Berlin to discuss the way forward but again, could not agree on the “terms of reference”. Guterres said it was the first time he had met with the two leaders jointly since Crans-Montana. The purpose was to “take stock”.

The UN noted in its year-end report that tensions had also increased over developments related to the fenced-off part of Famagusta, Varosha after it was announced in June that the Turkish Cypriot authorities would conduct an inventory study as a first step towards its potential reopening, followed by visits to the closed-off area by journalists and by four ministers from Turkey which were facilitated by Turkish Cypriot authorities.

2020

In late January, the United Nations special envoy for Cyprus Jane Holl Lute said “there’s growing scepticism as to whether reunification is still possible”. The UNSG noted in his year-end report that the decrease in intercommunal contacts, compounded by Covid restrictions, had posed significant challenges to efforts during the year.

The biggest shift was the election of anti-reunification candidate Ersin Tatar and the ouster of Mustafa Akinci as Turkish Cypriot leader in October, further setting back efforts and a change of tack on the Turkish Cypriot side towards a two-state solution.

Tatar had been elected ‘prime minister’ in 2019. He has been described by those Turkish Cypriots who know him as “very smart, extremely active and straightforward, quick-minded and innovative” with a “realistic outlook” and not afraid of having new ideas. Indeed, his new ideas embrace a two-state solution and recognition of the north’s sovereignty before any new negotiations can start.

- A morning with new Turkish Cypriot ‘premier’ Ersin Tatar

- Ersin Tatar is more middle-class Nicosia than Black Sea

After he moved from ‘prime minister’ to Turkish Cypriot leader in just over a year, Tatar not only wasted no time in turning the negotiations process on its head with his Ankara-backed ‘new ideas’ but he also greenlit the opening of the fenced-off part of Famagusta known as Varosha that had lain abandoned since 1974 in the most provocative manner that caused untold grief to thousands of Greek Cypriot refugees.

Tatar and Nicos Anastasiades did deign to meet on November 3, 2020 under the auspices of the UN. They went in with opposing positions and came out the same way. Tatar said however he was willing to participate in an informal five-party summit but that other ideas – Turkey’s ideas – ought to be put on the table as well.

2021

UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres announced in February his intention to invite all sides to a five-plus-one informal conference in Geneva to explore if common ground existed to negotiate a solution.

With the Covid-19 pandemic as a backdrop, the Cyprus issue was characterised by an interlocking set of relations between multiple conflicting parties that finally cleared a rocky path towards the Geneva conference from April 27 to 29, 2021.

It had taken four years since the failure at Crans-Montana to get there, that is everyone sitting in the same room. Guterres suggested at one point that the UN was open to hearing alternative visions for the future of Cyprus if the same vision was shared by the parties involved. Nicos Anastasiades and Ersin Tatar were the protagonists with the foreign ministers of Greece, Turkey and Britain.

After an intense three days in Geneva with the guarantor powers, the UN said there was not enough common ground for Cyprus negotiations to re-start but they would try again in the near future, according to UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres.

He said that the Turkish Cypriots feel that talks on a bizonal bicommunal federation (BBF) framework have been exhausted while Greek Cypriots feel that the talks should continue from where they left off in Crans-Montana in 2017 based on a federation. He added that Turkish Cypriots believe they have inherent sovereign equality, and the solution should be based on two states.

“The truth is that, in the end of our efforts, we have not yet found enough common grounds to allow for the resumption of formal negotiations in relation to the settlement of the Cyprus problem,” Guterres said. “But I do not give up”.

Both sides coasted along on the failure with the blame game in full swing and all Guterres was left to say was that it had been agreed to continue the dialogue, “with the objective of moving in the direction of reaching common ground, so as to allow for the start of formal negotiations” but with both sides now sitting in polar opposite positions, it would be a tough nut to crack.

In September, Tatar and Anastasiades met Guterres for a lunch on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly in New York. The only new thing on offer was the menu and perhaps the possibility that Guterres would appoint a new envoy as Jane Holl Lute was moving on.

The appointment of a new envoy became the new mantra on the Greek Cypriot side because there was nothing else to look forward to. In October, Anastasiades wrote to Guterres pleading for a new envoy but the UNSG obviously did not see the point at that moment in time. Indeed, it would take him another two years to get around to it.

2022

With a new failure behind us at Geneva in 2021 and no prospects of a new envoy, the year was a damp squib in terms of the Cyprus issue other than to fan the dying embers of two failed processes across two terms for outgoing president Nicos Anastasiades – Crans-Montana and Geneva.

With two months left, he declared in December that he had made “superhuman efforts” during his ten years in office, that he had managed to record significant progress with the then leader of the Turkish Cypriot community, Mustafa Akinci, now also gone, leaving the latter’s successor Ersin Tatar to declare that going forward, only sovereign equality and the equal international status of the Turkish Cypriots were negotiable.

The UNSG report mid-year pointed out that the Turkish Cypriot political landscape had been characterised by uncertainty and increasing polarisation while in the Republic, unofficial campaigning has started for the presidential elections scheduled for February 2023.

With the Turkish side digging its heels in and with Anastasiades packing his presidential bags, UN Special Representative Colin Stewart said the elections in February 2023 would now determine future prospects “for better or worse”. The UN representative has made several references to “last chances”.

2023

Nikos Christodoulides, a former foreign minister and apprentice of NIcos Anastasiades, is elected president in February as an independent with the backing of the smaller hard-line parties but not his political home of Disy, causing a major rift in the party founded by Glafcos Clerides and led by Anastasiades prior to 2013. Despite his dovish claims to want a settlement, he was often seen as a bit of a hawk during his years at the foreign ministry but has made all the right noises since his election.

He spent the entire first year in office calling on the UNSG to appoint a new envoy for Cyprus and the first half trying to secure an EU envoy but failed miserably in the latter.

In March, UN Under-Secretary-General Rosemary DiCarlo paid a flying visit on behalf of the UNSG to gauge the mood by meeting separately with the two leaders.

In May, Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan was re-elected setting the stage for some election stability as far as any negotiations might be concerned as the interlocuters were now firmly in place but the Turkish side spent the year repeating that a bi-zonal, bi-communal solution was no longer their objective, which was not promising at all.

In his July report, the UNSG said “any opportunities” must be seized. This was followed by a meeting between Christodoulides and Tatar at the anthropological laboratory of the committee of missing persons (CMP) later in the month, which was hailed as “a positive first step”.

A second step was attempted in September on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly in New York where hopes were high that the two leaders would meet jointly with the UNSG. However, the Turkish side backed out and it never happened.

They did however both attend on a social basis, the UN’s end-of-year dinner at the Ledra Palace and where everyone was full of good wishes for the new year.

2024

The long-awaited envoy was appointed in early January, kicking off the beginnings of a possible new process. UNSG Antonio Guterres appointed María Angela Holguin of Colombia as his personal envoy on Cyprus. He asked Holguín to assume a good offices role on his behalf to search for common ground on the way forward. The appointment was welcomed all round though probably less keenly in the north of the island but Ankara must have been on board since there was more grumbling rather than fussing over the appointment. The announcement came at the same time as Guterres’ latest report on Cyprus, which was fairly downbeat despite the inklings of a new process.

The new envoy arrived in Cyprus at the end of the month for her first visit. She said her job was to listen. After her meetings in Cyprus she headed for Athens, Ankara and the UK.

Holguin returned in March for further contacts with the two sides, expanding it to the political party leaders as well. Asked if there were any “positive signs” from her meetings so far, she said both sides were willing “to explore”, and that this was “a good thing”.

However, despite all the backslapping over the securing of a new envoy after two years of begging, neither of the two leaders attended a UN event in early March to mark 60 years of Unficyp in Cyprus. Perhaps they were just embarrassed by taking up UN resources for more than half a century. The official reason was that the Cyprus government wanted the reception to be attended solely by representatives of the Republic of Cyprus, which was the host state. The foreign ministry held its own event to press home the point.

At the boycotted UN event, Special Representative Colin Stewart said political courage to solve the Cyprus problem was in short supply and he appealed to the relevant actors to take the “tough decisions” needed.

Also in January, President Nikos Christodoulides announced a series of 14 unilateral confidence-building measures. Opposition Akel called them “low level” in terms of any policy or worth to the Cyprus negotiations. And let’s not forget that 2024 marks 50 years since the Turkish invasion.